May 6, 2025 | Chandler Sanchez with Travis Madsen

———————————————————-

With Congress returning from its April recess, House budget leaders are working in earnest on a reconciliation bill. To make room for extending the 2017 tax cuts, Congressional leaders have promised to cut $1.5 trillion from the federal budget over the next decade.

In the last post I wrote for the SWEEP blog, my colleagues and I explored what might happen if Congress were to look for some of that money by repealing federal electric vehicle (EV) tax credits. A key conclusion: the main point of EV tax credits are to point consumers towards options that save them money, strengthen our economy, and make our transportation system more energy- and cost-efficient. The savings on fuel and maintenance that EVs provide are worth far more than the investment the federal government is making through incentives. Tipping the market toward more efficient technology will make us all better off, to the tune of $2.7 trillion in national benefits through mid-century.

Over 200,000 miles, an EV driver in the Southwest could save as much as $36,000 in net present value terms. (That’s for an electric pickup in Nevada, where overnight home electricity rates are much cheaper than local gasoline prices). If the EV tax credit were not available, overall EV savings remain substantial in all cases across the Southwest, with the exception of small sedans in Wyoming, where off-peak discounted electricity rates are less common; electricity rates are closer to gasoline costs; and a $200 per year EV registration fee is in place. (Note that this analysis did not attempt to incorporate any impact of evolving tariff policy.)

Despite the fact that EVs make sound economic sense, federal purchase incentives are important to increase buyer awareness of the technology and potential for savings. Just how critical is that signal? Princeton’s REPEAT project estimated that without federal tax credits and without current federal fuel economy regulations, EV sales across the United States would be 40% less in 2030 (still growing, but not as fast).

In this report, we ask the question: How big of a missed opportunity would that be? How much money would drivers waste on inefficient vehicle technologies, unnecessary fuel consumption, and extra maintenance if Congress repealed federal EV tax credits? And how many jobs in our region might be lost?

Without federal EV tax credits, drivers lose out on savings

To answer this question, we made some simplifying assumptions. We based the analysis on a forecast of vehicle sales from 2025 through 2030 with and without the EV tax credit, developed by researchers at Princeton. We only looked at light-duty vehicles, not medium- or heavy-duty (which also are eligible for tax credits). We looked at the vehicle market in the Southwest as a whole, rather than attempting to parse out differences between states. And lastly, we estimated that a typical Southwest EV driver would save about $20,000 over a 200,000 mile vehicle lifetime, based on the work we did in our previous report. (See the Methodology section below for full details).

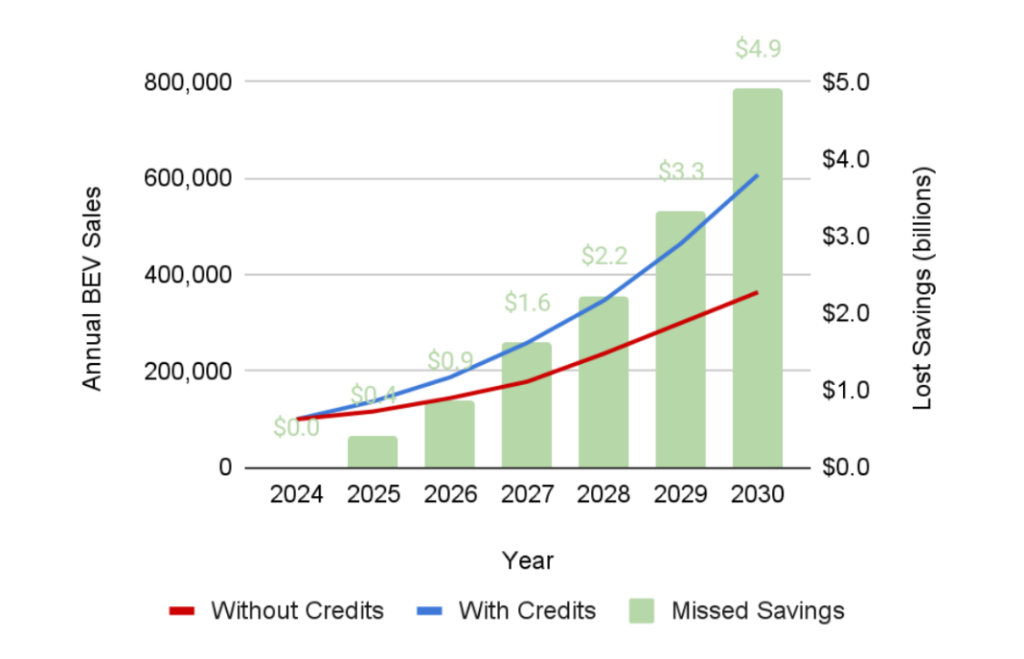

We estimate that consumers across the Southwest could lose out on more than $13 billion in transportation savings by 2030 if the Inflation Reduction Act tax credits are repealed. (That number represents the total net present value of missed savings over a 200,000 mile lifetime for vehicles purchased between 2025 and 2030. See the chart below for a visual summary of our results.)

While EV adoption will continue to grow, repealing the credits would increase the up-front cost of many EVs and make buying one less obviously attractive. Overall, the number of new EVs purchased in the Southwest from 2025 through 2030 would decline by about a third, from two million with the credit to about 1.3 million without the credit.

In other words, in a future without federal EV tax credits, consumers would buy about 700,000 inefficient combustion vehicles when they might have otherwise purchased electric models. Those purchasers would be locked into less-efficient technology and increased fuel and maintenance costs for the lifetime of those vehicles. Overall, the missed savings opportunity adds up to more than $13 billion that would otherwise be available for people in the Southwest to spend on other goods and services they need to take care of their families or run their businesses over the next several decades.

Without federal EV tax credits, EV sales in the Southwest would slow down significantly, reducing potential savings

Southwest states would also lose manufacturing jobs without EV credits

Many Southwestern States – especially Nevada and Arizona – are home to a growing domestic supply chain for battery supply chains, as well as some vehicle manufacturing. Planned investments in these facilities – and the jobs they are creating – would be less warranted if the pace of EV market growth slows in the absence of EV credits, putting current and future jobs at risk.

The International Council on Clean Transportation estimates that repeal of federal EV-related credits would result in the loss of more than 130,000 direct manufacturing jobs by 2030. And those are not just future jobs that haven’t been realized yet – more than 12,000 people that are doing EV-related work today would lose their jobs.

Nevada ranks fourth in the nation for potential job loss, with more than 10,000 positions at stake. Northern Nevada in particular is home to a developing battery industry, with activity from mining key materials like lithium; to technology development and battery assembly; to recycling and re-manufacturing. Northern Nevada also hosts one of Tesla’s gigafactories, where thousands of workers assemble vehicle components and where the Tesla Semi will be made.

Arizona ranks 13th nationally for potential job loss, with more than 3,500 jobs at risk. Major EV industry players have chosen Arizona for investments, including a $1.2 billion American Battery Factory facility near Tuscon expected to create as many as 1,000 jobs, and a huge $5.5 billion LG Solutions battery factory near Queen Creek set to open in 2026.

The Princeton REPEAT project concludes that “Without clean vehicle tax credits, between 29% and 72% of battery cell manufacturing capacity currently operating or online by the end of 2025 would be unnecessary to meet automotive demand and could be at risk of closure, in addition to 100% of other planned facilities.”

I think that fact is why Representative Mark Amodei (NV-02), Representative Juan Ciscomani (AZ-06), Representative Gabe Evans (CO-08), and Representative Mark Hurd (CO-03) signed a letter to House leadership in defense of federal clean energy tax credits; and why four U.S. Senators, including Senator John Curtis of Utah, recently signed a similar letter to Senate Majority Leader John Thune.

Rep. Amodei clarified at an event with EV industry leaders during the April recess that preservation of the EV credits was a bottom line for him: “The electric vehicle and battery technology stuff is not the future… it’s now,” Amodei said, as quoted by the Nevada Independent. “Pursuing those [opportunities] because it’s the right policy for your region and your people, regardless of whether you’re a donkey or an elephant or a wild horse or whatever you are, is a smart thing to do.”

Today, federal EV tax credits are pointing the Southwest towards jobs and prosperity – as well as the cost savings that come from a more efficient transportation system. We’ll find out soon if Congress will stay the course.

Methodology

We based our analysis on projected light-duty EV sales by the Princeton REPEAT project. Under a mid-range projection of current policy impacts (with EV tax credits intact), REPEAT predicts that nationally, EVs will make up just over half of the light-duty market in 2030.

In 2024, the six-state U.S. Southwest region that SWEEP covers (Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, Utah, and Wyoming) achieved a 10.9% light-duty EV market share, while the nation as a whole ended up at 8.6%, according to Atlas Public Policy. In other words, the Southwest was 27% ahead of the nation in light-duty EV sales.

Assuming the Southwest remains ahead of the nation as a whole by the same percentage as in 2024, EV penetration in the Southwest would be around two-thirds of the market in 2030.

Similarly, under the “Frozen Policies Benchmark” scenario developed by REPEAT, representing repeal of federal EV tax credits and fuel efficiency regulations, the national light-duty EV market share would be 31 percent in 2030. Assuming the Southwest remains ahead of the nation as a whole by the same percentage as in 2024, EV penetration in the Southwest would be around 40% of the market.

We took those market share projections and broke them down incrementally by year based on projected national volumes of electric vehicle sales under current policy, and under policy repeal, as presented on page 6 of the REPEAT project slide deck.1

We translated those market share figures into total sales of EVs by year based on a 2024 baseline as tracked by Atlas Public Policy, which showed that buyers in the Southwest registered about 100,000 new EVs in 2024, out of a total light-duty market size of 917,000 vehicles – making the simplifying assumption that the overall size of the light duty market would remain steady through 2030 at 2024 levels. We then calculated the difference in projected EV purchases by year from 2025 through 2030 by subtracting forecast EV sales in the policy repeal scenario from the current policy scenario.

We estimated typical average savings of an EV driver in the Southwest as follows: We began with vehicle lifetime total ownership savings data calculated for EV sedans, crossovers, pickup trucks, and SUVs in each Southwest state as described in our previous blog post. We then calculated the share of the total 2024 EV market aggregated across the full Southwest region represented by sales of each type of vehicle in each state, per Atlas Public Policy statistics. We then multiplied calculated lifetime EV savings for each type of vehicle in each state by its total share of the Southwest market in 2024, and summed the savings numbers. The result represents a weighted average of EV driver lifetime savings in net present value terms, weighted by the relative market share of each kind of vehicle in each Southwest state in 2024. We multiplied that value times the number of projected electric vehicle sales lost in each year from 2025 through 2030 as described above to estimate net present value of missed savings. We then calculated total estimated missed savings by adding the net present value of missed savings from each individual year from 2025 through 2030.

- Jenkins, J. (2025). Potential Impacts of Electric Vehicle Tax Credit Repeal on US Vehicle Market and Manufacturing. REPEAT Project. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15047921 ↩︎